The Dalkey Archive Press is a small but well-respected publisher of contemporary and experimental literature, founded in 1984, with offices in Champaign, London and Dublin. It specialises in literature in translation and boasts a formidable list of writers, including: Huxley, Barthelme, Djuna Barnes, Robbe-Grillet, Fuentes and Nicholas Mosley. If you are in any way interested in modern and challenging literature throughout the world, then the Dalkey Archive Press is a brand to look out for on the shelves of your local bookstore.

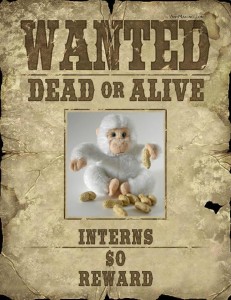

“has begun the process of succession from the founder and current publisher, John O’Brien, to a publishing house that will be directed by two-three people along with support staff. With the recent decision to expand our London office and make London the base of European operations, the Press seeks to develop its staff there. Who will take on leadership positions at the Press over the next few years will be the result of this transitional process. The pool of candidates for positions will be primarily derived from unpaid interns in the first phase of this process, although one or two people may be appointed with short-term paid contracts.”

“do not have any other commitments (personal or professional) that will interfere with their work at the Press (family obligations, writing, involvement with other organizations, degrees to be finished, holidays to be taken, weddings to attend in Rio, etc.)”

[…]we seek people who know what a job is[…]

[…]are able to learn quickly, are dedicated to doing excellent work, can meet all deadlines, and happily take on whatever needs to be done. Attitude and work habits, along with various skills, are just as important as experience and knowledge.[…]

[…]Any of the following will be grounds for immediate dismissal during the probationary period[…]

[…]being unavailable at night or on the weekends; failing to meet any goals; giving unsolicited advice about how to run things;[…]

[…]creating an atmosphere of complaint or argument[…]

[…]not showing an interest in other aspects of publishing beyond editorial; making repeated mistakes.[…]

“By the end of–or even sooner–of the internship/trial period, both the candidate and the Publisher should know that the Press needs the person and would be making a major mistake not to maintain the person for the future.”

“Assume that you will begin to be evaluated as soon as your application arrives. And also assume that you will be one of the unpaid interns until you are ready to take on all the responsibilities of a position. Incomplete applications will not be considered. We will not be able to acknowledge receipt of applications or provide feedback about your application. We will contact only those people whom we wish to ask further questions of or that we intend to interview. Do not contact us about your application.“

Dalkey Archive Press founder, John O’Brien responded to the Irish Times following the posting of the intern positions:

“The advertisement was a modest proposal. Serious and not-serious at one and the same time. I’ve been swamped with emails (I wish they’d stop: I’ve work to do), and with job applications. I certainly have been called an ‘asshole’ before, but not as many times within a 24-hour period.”

Nice turnaround, John. Serious but non-serious. I’d suggest you stop digging a bigger hole for yourself!

UPDATE:

This story has been picked up by Twitter and a number of media outlets including the LA Times under the headline: Dalkey Archive posts world’s wackiest job listing. Quite a few comments cite the US Fair Labor Standards Act for internships. The one caveat I would add to this is that Dalkey is a non-profit organisation! My beef is how utterly appalling and unattractive these job internships would be to prospective candidates, not to mention the demeaning tone of the communication itself. Me thinks there is something of a re-spin being played out by John O’Brien of Dalkey. Internships should be for the benefit of the candidate, not solely the employer, whether there is or isn’t a job possibility at the end of it.

However, on a lighter note, the parody has begun! https://twitter.com/DalkeyIntern

I once accidentally read a book that wasn’t published by the Dalkey Archive. When I realised what I’d done, I cried for hours.

— Dalkey Intern (@DalkeyIntern) December 13, 2012

When I first read Djune Barnes’ Nightwood, the first thing I thought was, ‘I’m going to work for free in an office and do lots of admin.’

— Dalkey Intern (@DalkeyIntern) December 13, 2012

Who needs money or food? How petty and bourgeois. All I need is oxygen, avant-garde literature, and the constant threat of unemployment.

— Dalkey Intern (@DalkeyIntern) December 13, 2012

FOR SALE Avant garde press. Forced sale due to confusion with satire & irony $100 ono. No tyre-kickers. Intern buyers welcome #dalkeyintern

— TIPM (Mick Rooney) (@MickRooney7777) December 13, 2012

Internship Programs Under The Fair Labor Standards Act

This fact sheet provides general information to help determine whether interns must be paid the minimum wage and overtime under the Fair Labor Standards Act for the services that they provide to “for-profit” private sector employers.

Background

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) defines the term“employ” very broadly as including to “suffer or permit to work.” Covered and non-exempt individuals who are “suffered or permitted” to work must be compensated under the law for the services they perform for an employer. Internships in the “for-profit” private sector will most often be viewed as employment, unless the test described below relating to trainees is met. Interns in the “for-profit” private sector who qualify as employees rather than trainees typically must be paid at least the minimum wage and overtime compensation for hours worked over forty in a workweek.*

The Test For Unpaid Interns

There are some circumstances under which individuals who participate in “for-profit” private sector internships or training programs may do so without compensation. The Supreme Court has held that the term “suffer or permit to work” cannot be interpreted so as to make a person whose work serves only his or her own interest an employee of another who provides aid or instruction. This may apply to interns who receive training for their own educational benefit if the training meets certain criteria. The determination of whether an internship or training program meets this exclusion depends upon all of the facts and circumstances of each such program.

The following six criteria must be applied when making this determination:

- The internship, even though it includes actual operation of the facilities of the employer, is similar to training which would be given in an educational environment;

- The internship experience is for the benefit of the intern;

- The intern does not displace regular employees, but works under close supervision of existing staff;

- The employer that provides the training derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the intern; and on occasion its operations may actually be impeded;

- The intern is not necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of the internship; and

- The employer and the intern understand that the intern is not entitled to wages for the time spent in the internship.

If all of the factors listed above are met, an employment relationship does not exist under the FLSA, and the Act’s minimum wage and overtime provisions do not apply to the intern. This exclusion from the definition of employment is necessarily quite narrow because the FLSA’s definition of “employ” is very broad. Some of the most commonly discussed factors for “for-profit” private sector internship programs are considered below.

Similar To An Education Environment And The Primary Beneficiary Of The Activity

In general, the more an internship program is structured around a classroom or academic experience as opposed to the employer’s actual operations, the more likely the internship will be viewed as an extension of the individual’s educational experience (this often occurs where a college or university exercises oversight over the internship program and provides educational credit). The more the internship provides the individual with skills that can be used in multiple employment settings, as opposed to skills particular to one employer’s operation, the more likely the intern would be viewed as receiving training. Under these circumstances the intern does not perform the routine work of the business on a regular and recurring basis, and the business is not dependent upon the work of the intern. On the other hand, if the interns are engaged in the operations of the employer or are performing productive work (for example, filing, performing other clerical work, or assisting customers), then the fact that they may be receiving some benefits in the form of a new skill or improved work habits will not exclude them from the FLSA’s minimum wage and overtime requirements because the employer benefits from the interns’work.

Displacement And Supervision Issues

If an employer uses interns as substitutes for regular workers or to augment its existing workforce during specific time periods, these interns should be paid at least the minimum wage and overtime compensation for hours worked over forty in a workweek. If the employer would have hired additional employees or required existing staff to work additional hours had the interns not performed the work, then the interns will be viewed as employees and entitled compensation under the FLSA. Conversely, if the employer is providing job shadowing opportunities that allow an intern to learn certain functions under the close and constant supervision of regular employees, but the intern performs no or minimal work, the activity is more likely to be viewed as a bona fide education experience. On the other hand, if the intern receives the same level of supervision as the employer’s regular workforce, this would suggest an employment relationship, rather than training.

Job Entitlement

The internship should be of a fixed duration, established prior to the outset of the internship. Further, unpaid internships generally should not be used by the employer as a trial period for individuals seeking employment at the conclusion of the internship period. If an intern is placed with the employer for a trial period with the expectation that he or she will then be hired on a permanent basis, that individual generally would be considered an employee under the FLSA.